Drowning and Diving:

What’s Useful for Scuba Divers to Know

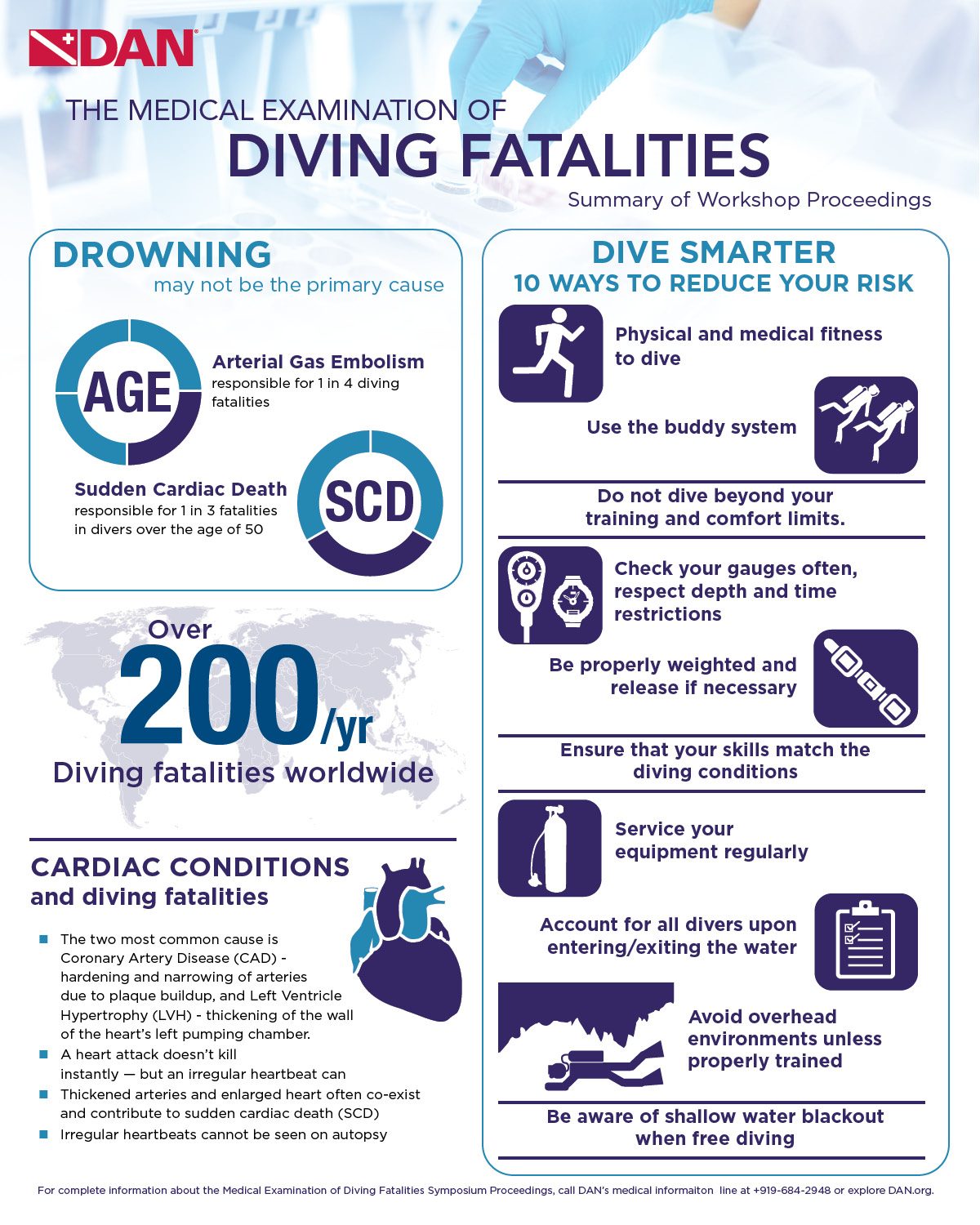

Drowning is often listed as a leading cause of death in diving accidents, however experts state that there are usually other causes. Read more about the issues with identifying drowning and other causes here: https://dan.org/health-medicine/health-resource/health-safety-guidelines/medical-examination-of-diving-fatalities/

Drowning is often listed as a leading cause of death in diving accidents, however experts state that there are usually other causes. Read more about the issues with identifying drowning and other causes here: https://dan.org/health-medicine/health-resource/health-safety-guidelines/medical-examination-of-diving-fatalities/

A Clear Definition for Divers

Drowning is

the process of experiencing respiratory impairment from

submersion/immersion in liquid.

From the World Congress on Drowning in 2002; later published in: van Beeck EF, Branche CM, Szpilman D, Modell JH, Bierens JJ. A new definition of drowning: towards documentation and prevention of a global public health problem. Bull World Health Organ. 2005 Nov;83(11):853-6.

In simple terms, this means a person is unable to breathe properly—either because water is blocking their airway and forced to breath-hold, or water inhaled and airway closed. Submersion or immersion refers to the nose and mouth being in or under water, whether fully or partially. This definition emphasises that drowning is a process that happens when breathing is impaired in water—it does not refer to the outcome. Whether the person survives or dies comes later; the term “drowning” itself describes the breathing difficulty that results from being in/under water (or other liquid).

What are the outcomes of drowning?

According to international guidelines, drowning has three possible outcomes:

Fatal drowning – the person dies.

Non-fatal drowning with morbidity – the person survives but experiences injury (e.g. lung damage, brain injury).

Non-fatal drowning without morbidity – the person survives without lasting physical effects.

Why does this definition of drowning matter for scuba divers?

Drowning doesn’t have to be fatal. The term applies to anyone who experiences breathing difficulty due to water entering the airway—regardless of whether they survive.

This modern definition replaces older, misleading terms like near-drowning, dry drowning, and secondary drowning, which are now considered outdated and inconsistent. (e.g. British Medical Journal, 2025 https://bestpractice.bmj.com/topics/en-gb/657)

It highlights that even brief breathing impairment counts as drowning—for example:

During a panic response at the surface or underwater

Delays or obstructions in gas-sharing, switching regulators or loss of regulator

If a diver inhales water accidentally during equipment use or mask clearing

A diver may survive the incident but still face medical consequences (such as pulmonary issues) or psychological impacts (such as anxiety, avoidance, or panic on future dives).

It clarifies that if someone is in difficulty in the water but breathing is not impaired, then it is not drowning—it’s a water rescue. (British Medical Journal,2025 https://bestpractice.bmj.com/topics/en-gb/657)

Understanding drowning as a process with a range of outcomes helps divers, instructors, and health professionals better recognise and respond to incidents.

The third leading cause of unintentional injury death worldwide, (United Nations).

Drowning is a serious global health concern, with estimates suggesting that more than 30 lives are lost to drowning every hour, and close to 300,000 people died from drowning in 2021, (WHO 2024 Global Report on Drowning Prevention).

Nearly half of all drowning deaths involve individuals under the age of 29, with about one in four occurring in children under 5. Young children are particularly vulnerable, especially when they are unsupervised around water (WHO 2024 Global Report on Drowning Prevention).

Globally, the vast majority of drowning deaths—around 90%—occur in low- and middle-income countries. (WHO 2024 Global Report on Drowning Prevention).

Most drowning deaths are preventable through measures like supervision, barriers, water safety education, and rescue training.

"An average of 328 UK and Irish Citizens lose their life to accidental drowning EVERY YEAR and many more have non-fatal experiences, sometimes suffering life-changing injuries. Royal Life Saving Society.

World Health Organization (WHO) – Global leadership on public health, including drowning prevention policy and data. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/drowning

International Life Saving Federation (ILS) – Global federation of lifesaving and water safety organisations. https://www.ilsf.org/drowning-prevention/

Royal Life Saving Society UK (RLSS UK) – UK’s leading charity for lifeguarding and water safety education. https://www.rlss.org.uk/Pages/Category/water-safety-information

Royal National Lifeboat Institution (RNLI) – Provides coastal rescue services and public education campaigns on drowning prevention. https://rnli.org/safety

Swim England – Promotes learn-to-swim programmes and supports school-based water safety education.

National Water Safety Forum (NWSF) – UK coalition of organisations including RNLI, RLSS, and others, coordinating national water safety strategy https://www.nationalwatersafety.org.uk/campaigns

If you require urgent assistance or medical help for a diving incident in the UK / UK resident.

COASTGUARD - For immediate assistance, rescue and urgent medical help on the water or suspected diving injury/illness, contact the Coastguard via Channel 16 or phone 999 and ask for the coastguard.

24hr National Diving Accident Helpline - England & Wales 07831 151 523; Scotland 0354 408 6008

Medical Advice Helpline - DDRC (24hrs) for health worries as a result of diving 01752 209 999

[DAN Europe Members] Emergency Hotlines - Diving Accidents out of the UK call DAN Europe International Hotline +3906 42 11 5685 or in the UK Midlands Diving Chamber/DAN Europe National Emergency Hotline 07931 472 602

For a small number of people learning to dive, certain skills trigger an unexpectedly strong stress reaction. This response is sometimes linked to a past non-fatal drowning, often in childhood.

As a scuba diving instructor, a pattern that many of us observe occassionally is a diver-in-training who appears confident and has no history of difficulty—until a specific skill triggers an unexpected and intense stress response. This is most commonly seen with mask and regulator skills.

The diver suddenly panics or refuses to continue.

The stress seems out of proportion to the task.

Only afterward does the diver recall or disclose a past drowning event.

Sometimes, they remember the incident for the first time during training.

Drowning is common, especially in childhood. The World Health Organization estimates hundreds of thousands of non-fatal drowning incidents each year. Many involve children who are rescued quickly and may not even receive medical attention.

These experiences often go unrecognised as traumatic, especially if the child “seemed fine” afterwards. But from a psychological perspective, the overwhelming fear, loss of control, and sense of helplessness are key features of trauma.

When a diver later practises underwater skills that simulate loss of air, water in the nose, or impaired vision, it can activate unprocessed trauma memories—emotional and bodily reactions stored in the nervous system, even if the person had not previously been bothered by the event.

This helps explain why some divers:

Have no issues until they reach a particular skill that brings on fear, panic, or tears

Only later remember a childhood experience of nearly drowning—being pulled out of a pool or panicking in the sea

May never have thought of it as trauma, but still experience a strong fight/flight response underwater

This isn't a sign of weakness or poor instruction. It’s a normal human response to a past threat the brain and body still recognise.

For some divers, this unprocessed memory of drowning becomes a real barrier to progress:

Repeated panic or shutdown during specific skills

Growing avoidance or loss of confidence

In some cases, abandoning training altogether

Unless this underlying trauma is acknowledged and addressed, repeated exposure to triggering dive situations can actually reinforce the fear and make it harder to move forward. This can sometimes lead to certified divers who are uncomfortable with important skills, and therefore at risk of getting into difficulties when diving.

Exploring how behaviour, equipment, and the diving environment can interact in ways that increase vulnerability

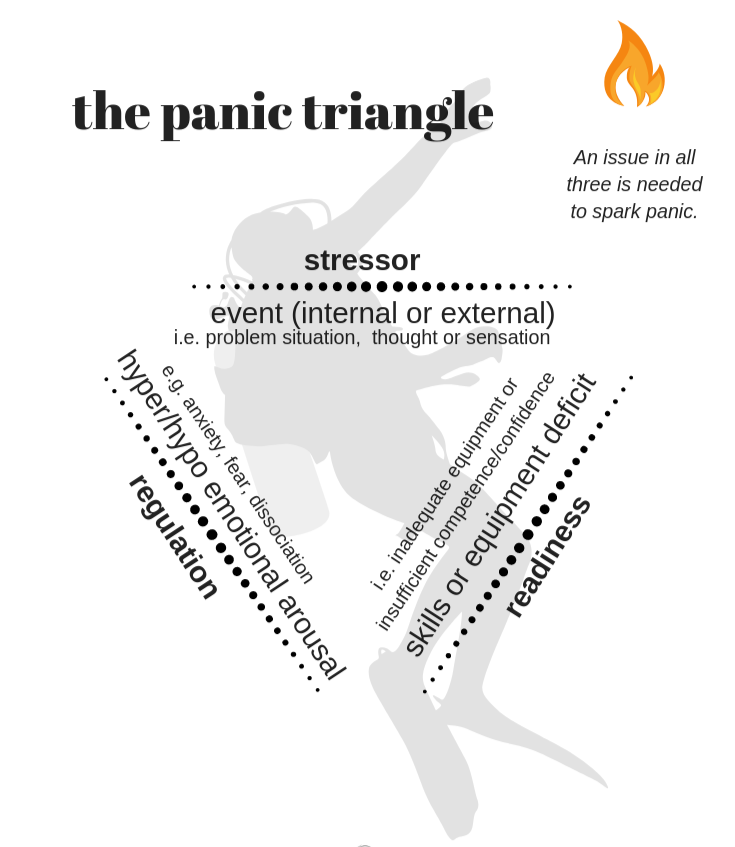

Drowning in scuba diving rarely comes out of nowhere—it often develops from a complex interaction of stress, skill gaps, and emotional overwhelm. In many cases, the diver encounters a stressor—such as entanglement, disorientation, or a sudden worry about air supply. If they lack the readiness to respond (for example, difficulty with mask clearing, buoyancy control, or air-sharing), and struggle with regulating their emotions, panic can quickly take over. This is where things can unravel: panic may lead to dropping the regulator, uncontrolled ascent, or gas depletion—any of which can result in drowning.

These elements—readiness, emotion regulation, and the stressor—form what’s known in diving psychology as the Panic Triangle. Understanding and addressing each side of this triangle is a powerful way to reduce risk.

Drowning doesn't always look like what you see in films. In real life—and especially in diving—it’s often quiet, quick, and easy to miss. Recognising the signs early can be life-saving.

According to Divers Alert Network, people who are drowning often cannot call for help, wave, or splash dramatically. Instead, they may show subtle or even silent signs of distress.

Quiet or glassy-eyed appearance

Vertical in the water with no kicking

Head tilted back, mouth open

Attempting to swim or roll over without making progress

Gasping or hyperventilating

Regulator out, struggling to breathe or speak

Weak or ineffective arm signals; or struggling with equipment

Kit can be part of the problem! An underinflated BCD, over-weighting or entanglement with ditched weights

Silent, passive, or drifting away from the group - possibly sinking unnoticed

Unresponsive to buddy or hand signals

Wide eyes or rapid, uncoordinated movements

Panic swim, rapid ascent, or uncontrolled descent

Losing or removing the regulator

Remaining motionless and not responding

Recognising the signs early and responding quickly can save lives. One of the best ways to prepare is by completing a CPR and first aid course, especially one focused on aquatic or diving-related scenarios. These courses help you learn what to look for, when to act, and how to respond safely and effectively. You’ll gain practical skills in recognising distress, performing rescue breaths, and using emergency oxygen—tools that could make all the difference.

👉 Look for a course from your local dive centre, training agency, or water safety organisation.

Even if someone seems fine, symptoms can develop hours later— seek medical help after drowning. (List from StatPearls https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK430833/ last update 2023).

Shortness of breath or difficulty breathing

Persistent coughing or chest tightness

Unusual fatigue or extreme tiredness

Irritability, confusion, or sudden changes in behaviour

Bluish lips or skin