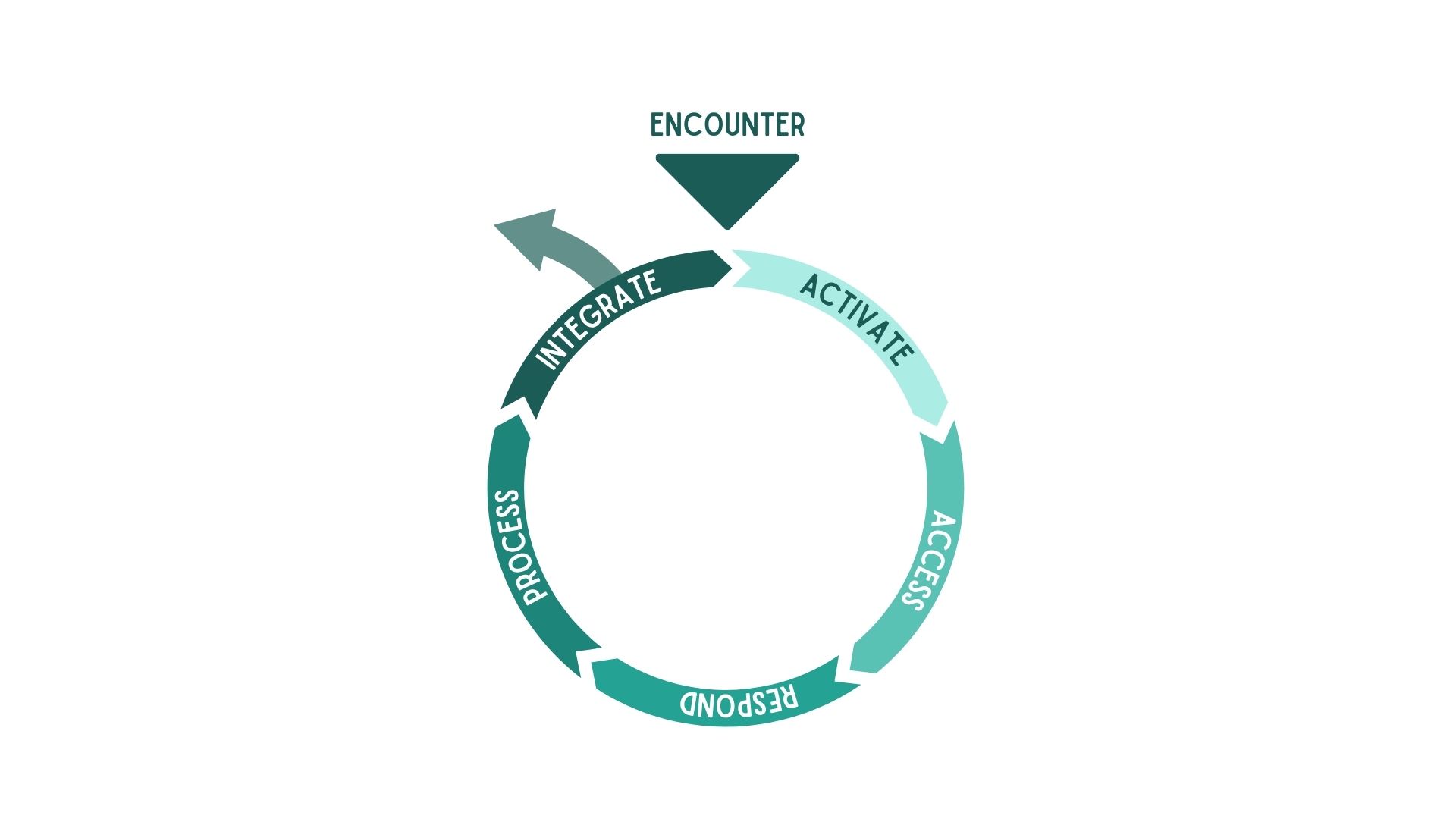

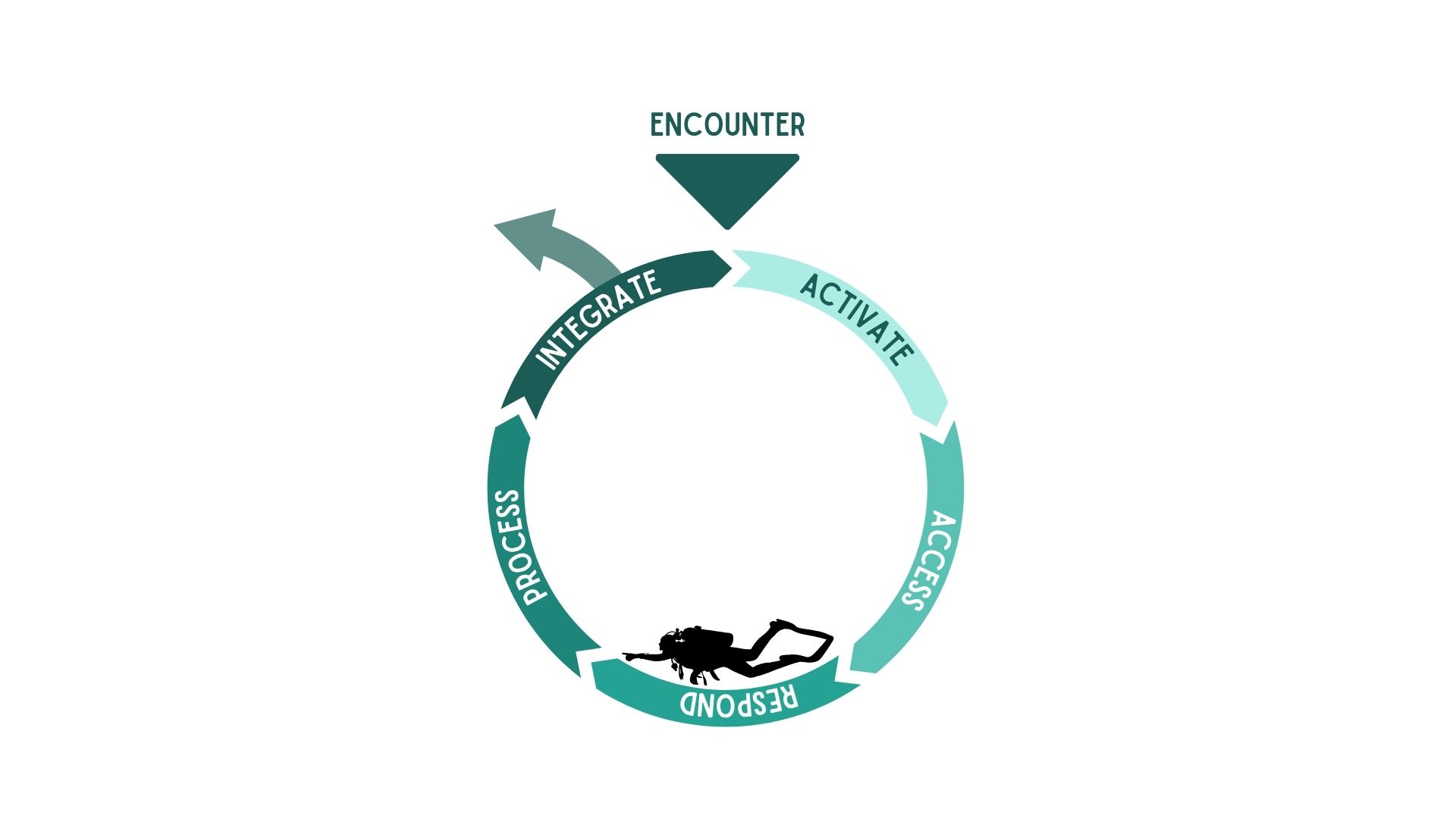

The Adaptive Loop

How we adapt to what we encounter in the diving environment

The adaptive loop is a way of understanding how we respond to the world around us, not just in moments of difficulty, but in everyday interactions, learning, and growth. It describes how we encounter something in our environment, register it, access what we know, respond to it, and then process and integrate the experience. This loop helps explain how adaptation happens: how we gradually become more attuned, more skilled, and more prepared over time.

The model draws on two key areas of influence. The first is the Adaptive Information Processing (AIP) model, developed by Francine Shapiro, which underpins Eye Movement Desensitisation and Reprocessing (EMDR) therapy and offers a framework for how the mind stores, updates, and reprocesses information. A second area of influence is cyclical learning models, which describe how people reflect on experience and apply learning. Here I’ve drawn from the work of Kolb and Honey and Mumford, who have each explored learning as a dynamic, cyclical process.

My version of the adaptive loop brings together elements of both and offers a practical way to understand change, learning, and personal development. It can be used as a general model of learning and adaptation. We can use these ideas in scuba diving, where it helps explain skill development, performance blocks, and recovery from difficult experiences. It forms the basis of how I support divers in becoming more confident, capable, and psychologically fit to dive.

An encounter is anything that draws your attention — something you see, feel, hear, or even imagine. It could be a situation underwater, a moment in your gear check, or a sensation in your body. You might encounter a leaky mask, a sudden current, or the realisation that you’ve gone deeper than expected. Encounters can be positive, neutral, or challenging.

In diving, many small encounters happen all the time. You feel a temperature drop. You hear your buddy signal. You notice you’re breathing a bit faster. These are all points of contact between you and your environment. Sometimes, if a diver feels uncomfortable with certain scenarios — like a mask flood — they might attempt to avoid those encounters entirely. This could take the form of telling themselves it won’t happen, becoming overly focused on equipment choice, or hoping that conditions will be gentle enough to reduce the risk. But avoidance keeps the stressor at bay only temporarily — and it also prevents learning and growth.

Activation is what happens inside you when your nervous system (brain etc.) registers that something is happening. It could be as subtle as a slight shift in attention or a tiny change in muscle tone — or as obvious as a rush of adrenaline. Sometimes it’s so slight that you don’t consciously notice it at all — your body adjusts, your awareness shifts, and you access "muscle memory" and respond smoothly without even thinking about it. Other times, activation is stronger: your breathing might change, your heart rate rises, or you suddenly feel very alert. It’s your nervous system getting ready to respond.

In diving, activation might show up when you notice your fin brushing a surface, hear an unfamiliar sound, or sense that something’s changed. These small alerts keep you tuned into your environment. But if the system becomes overwhelmed — like when a diver has had a past scare or is feeling underprepared — activation can spike too high or too fast. This can tip into anxiety, panic, or freeze. On the other end of the spectrum, activation can also drop too low — a kind of shutdown where nothing registers, even when something needs attention. Both extremes can block the rest of the adaptive loop from working.

Access is the point where your brain reaches into what you already know — your training, your past experiences, your beliefs, and your habits. You’re drawing on your memory networks to make sense of what’s happening and figure out what to do. In diving, this might mean remembering your mask clearing technique, or mentally rehearsing your ascent plan. When things go well, you access exactly what you need in that moment.

But sometimes, especially if you’ve had difficult experiences in the past, your brain accesses unhelpful or unprocessed material instead. You might remember a previous panic, or have a belief like “I can’t do this” come to the surface. In that case, your system might get stuck looping in old fears or sensations, even if the current situation is manageable. That’s when access doesn’t move you forward — it pulls you into a stuck place instead of preparing you to respond.

This is the action part of the loop: the point at which you do something to respond to a situation. It could be a physical action (e.g. adjusting your buoyancy), a communication (e.g. signalling your buddy), or an internal strategy (e.g. steadying your breathing). It could also include inner behaviour such as calming self-talk, a mental activity that is not visible on the outside. Responding is the test of whether the system has accessed something (potentially) useful and is able to engage with the situation.

Whatever the response is, that is the response. Sometimes it’s effective and resolves the situation; other times it may not work or may even make things more difficult. Either way, the person is still in the loop. As long as the diver remains engaged and continues through the cycle, even an imperfect or mistaken response can support learning and growth.

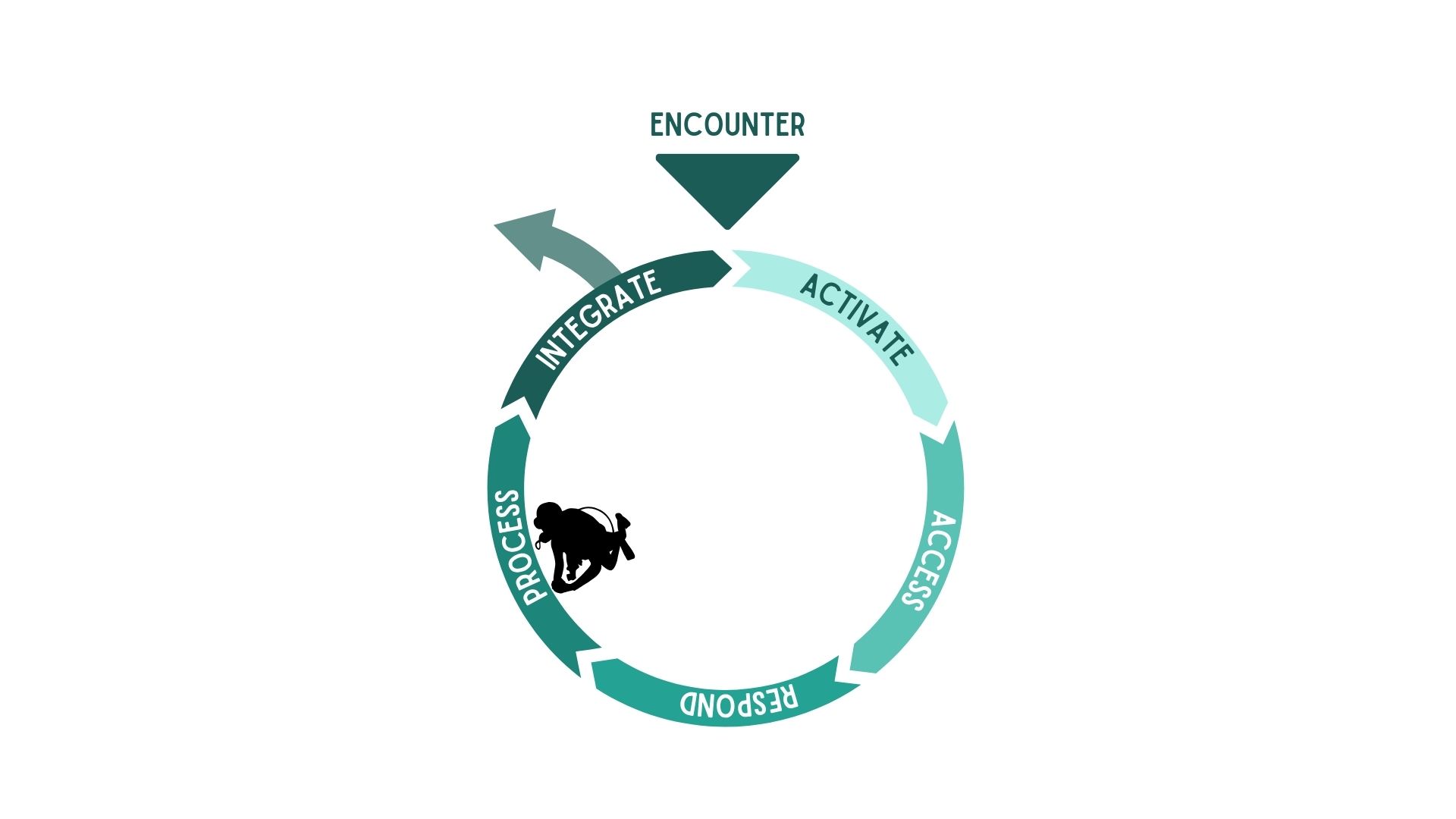

Processing describes how the brain filters, organises, and stores information about what just happened during the encounter, including how we ourselves responded. It may involve thoughts, sensations, emotions, or shifts in understanding. Some of this happens consciously, but much of it takes place automatically, below the level of awareness. Processing is where meaning is made and learning starts to take shape.

When the system is processing well, the experience starts to settle. New connections may form, and the experience gets woven into the wider network of what you know. But sometimes processing draws on old or unhelpful material, especially if the experience activated unresolved patterns or was traumatic. In those cases, it can take the form of harsh self-criticism, brushing off the event, or shutting down altogether. This makes it harder for the experience to be digested in a useful way.

The brain is always processing experience, and does that without our involvement. We can support useful processing with practices like post-dive debriefs, logging dives, or even quiet personal reflection can help bring parts of this process into awareness and guide it in a helpful direction. These small habits make it more likely that what was learned becomes available next time.

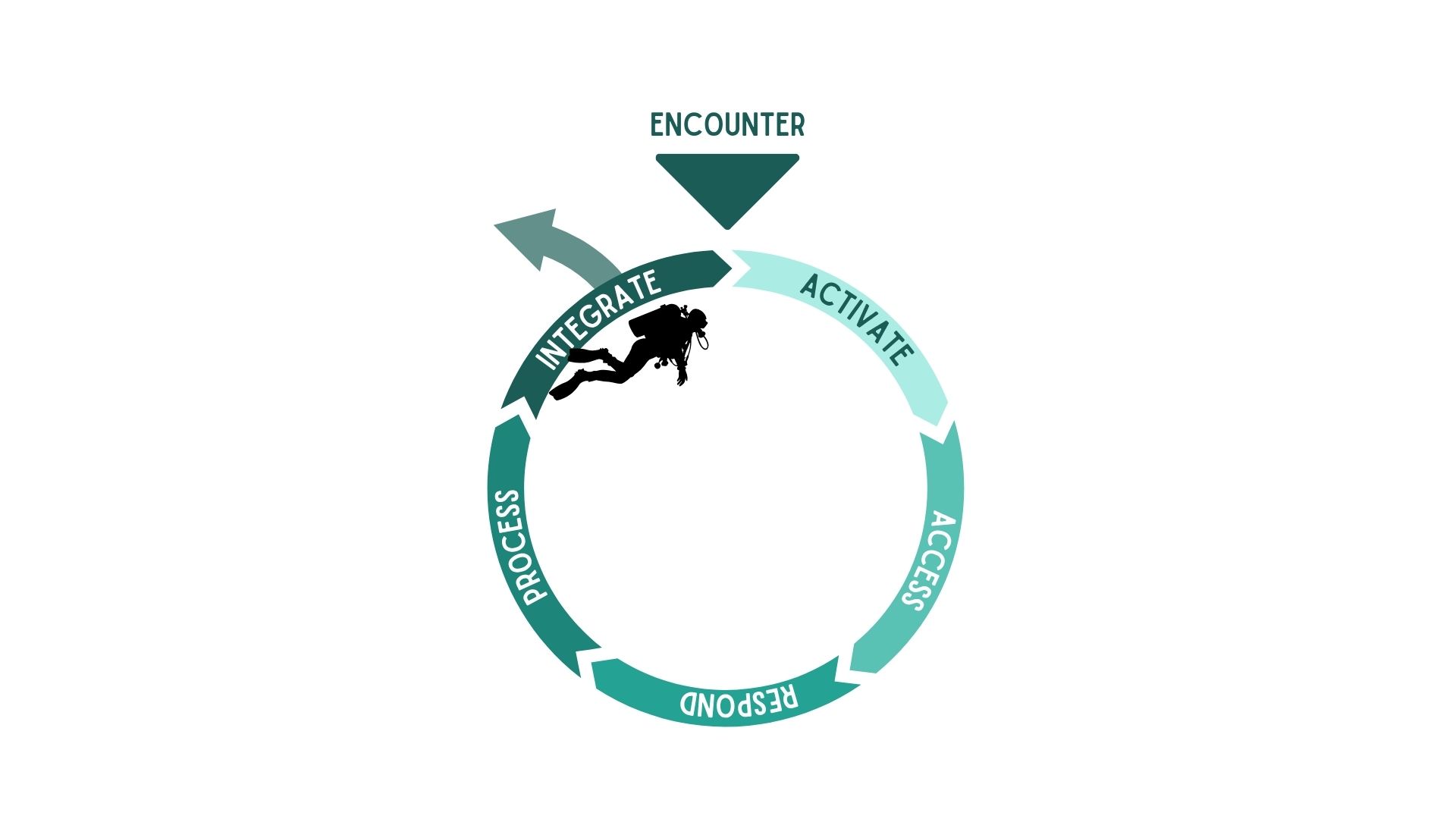

Integration is the point where the experience becomes part of your system. You carry it with you, not as baggage, but as part of your skillset. Integration might show up as new confidence, sharper awareness, or a more refined sense of what matters. It’s the quiet update that makes you more prepared for next time. You might not even notice it happening — but over time, these integrations shape who you are as a diver.

The more integrated your learning becomes, the more available it is when new situations arise. This is what builds intuition, judgment, and adaptability. Sometimes, full integration means we never encounter the same event/situation again — not because it couldn’t happen, but because we’ve adapted so well that we’ve changed our systems. For example, lessons learned from running out of air might lead to more robust checks, planning, and awareness that make a repeat far less likely. In other cases, like deploying a DSMB, we might repeat the skill on every dive and each time we repeat the loop, we may fine-tune our learning even further.

Adaptation happens every time we engage, reflect, and carry learning forward. This process is how we grow, encounter by encounter, becoming more attuned to ourselves and our environment. It's a way of understanding how learning, resilience, and change unfold over time.

We become divers over time, encounter by encounter, until comfort and confidence become part of how we move through the water.

This loop reflects a natural pattern that underlies not just diving, but many aspects of human development. When the process is working well, our systems take in information, respond flexibly, and consolidate experience in ways that prepare us for the future. We don’t have to think about it. It’s happening all the time, in ways both seen and unseen.

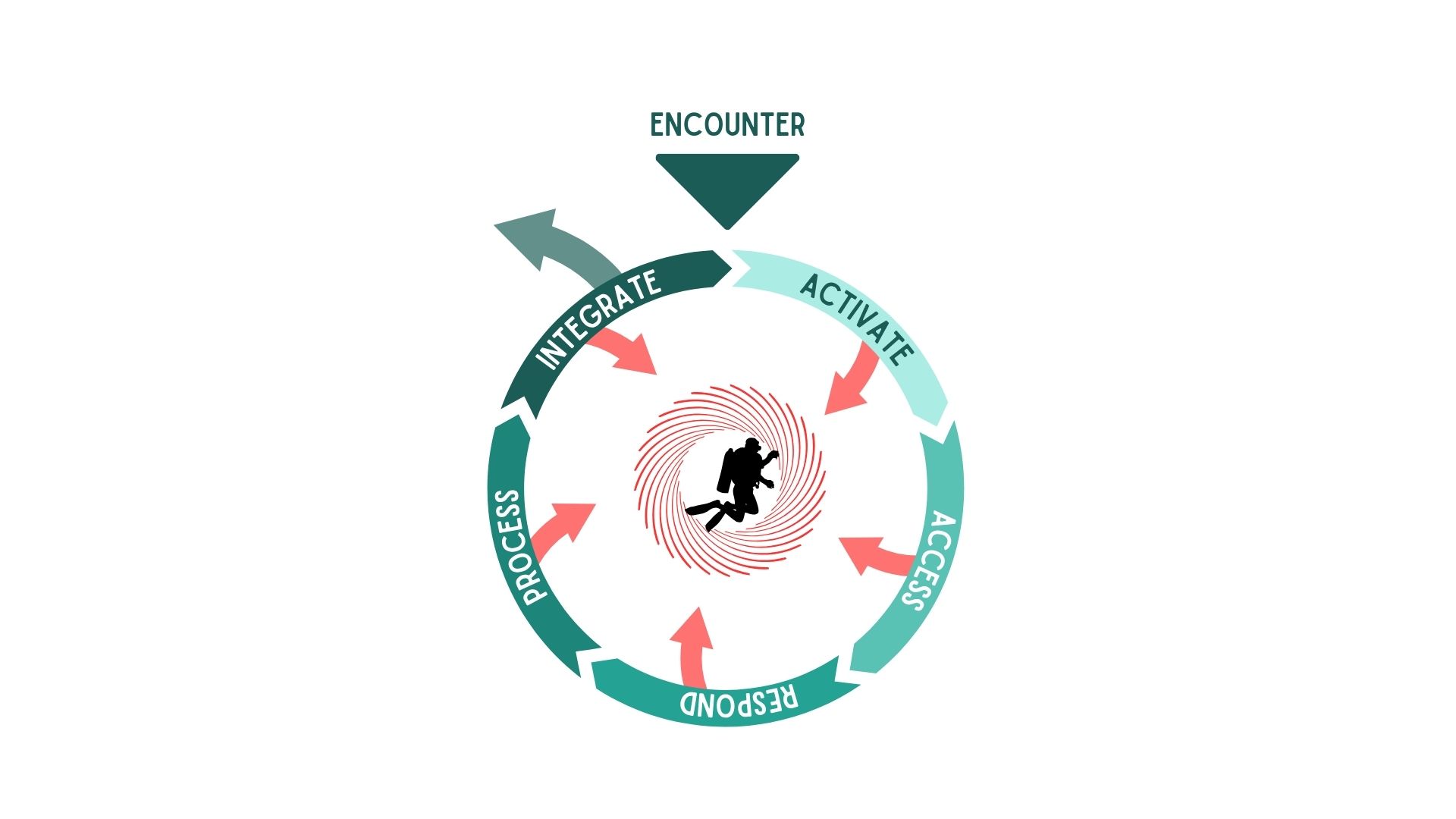

Sometimes, though, something disrupts the cycle. That could be a past experience that hasn’t been fully processed, a moment where we freeze instead of respond, or a pattern of avoiding particular encounters. When that happens, we fall out of the adaptive networks and get stuck in the maladaptive networks: old beliefs, behaviours and emotions that have not been integrated. These can come from past negative or distressing experiences, such as poor experiences of learning at school, or memories of DSMB delpoyments gone badly wrong. We might notice this as anxiety, frustration, hesitation, or feeling like we “should” be able to do something but can’t.

These sticking points can happen at any part of the loop, and often without us realising it. You might be doing your best to respond to a situation, but the response isn’t working, or it leaves you feeling more depleted than before. Over time, these disruptions can accumulate and show up as difficulty with specific skills, environments, or types of dives. In these moments, some extra support is often needed to help re-engage the system and restore a sense of flow.

There are many ways to support adaptive processes, from simple practices to therapeutic approaches. Skills like breathwork, mental rehearsal, and reflection can all help keep the loop moving, making it easier to respond effectively and build confidence over time. Alternatively, structured support such as debriefing, skills coaching, or Eye Movement Desensitisation and Reprocessing (EMDR) therapy can help unstick patterns that have become entrenched. Understanding how this loop works gives us options. It helps us recognise where we are, where we might be getting stuck, and how to reconnect with the parts of ourselves that are already trying to adapt.